Artists

- 19th Century

- Winslow Homer

- Utagawa Hiroshige

- Currier & Ives

- John Singer Sargent

- Impressionists & Post-Impressionists

- Camille Pissarro

- Auguste Renoir

- Pierre Bonnard

- Mary Cassatt

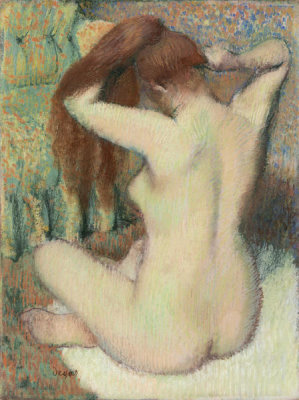

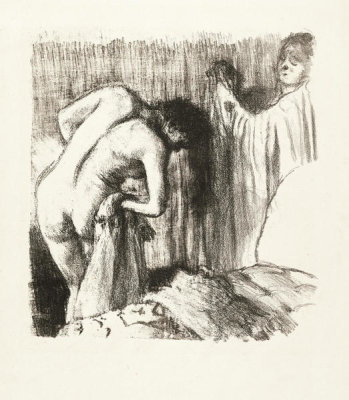

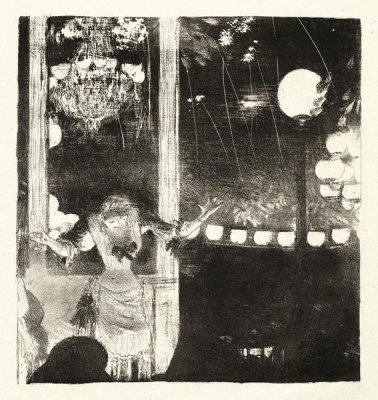

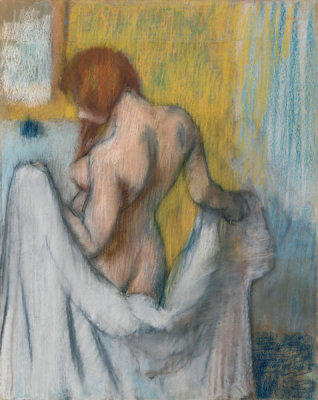

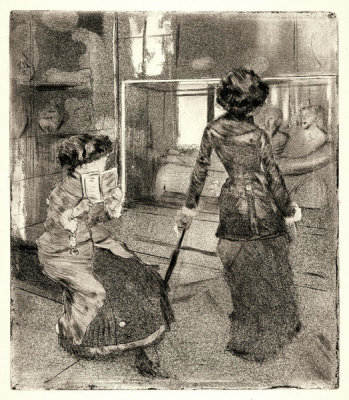

- Edgar Degas

- Paul Cézanne

Your Met Custom Prints order supports The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Subjects

- Waterscapes and Landscapes

- Waterscapes

- Landscapes and Scenery

- Cityscapes

- Ocean

- Countryside

- Lakes and Ponds

- Mountains

- Rivers

- Prairies and Fields

Prints and framing handmade to order in the USA.

Custom Framed

All framed items are delivered ready-to-hang

Featured Collections

- Featured Movements

- Harlem Renaissance

- Impressionism & Post-Impressionism

- Modernism

- Realism

- Romanticism

- Neoclassical

- Decorative Arts

- Across Cultures

- American Art

- Asian Art

- European Art

Individually made-to-order for shipping within 10 business days.

Hand-crafted

Made to your specifications

Best Sellers

- Vincent van Gogh, Wheat Field with Cypresses

- Emanuel Leutze, Washington Crossing the Delaware

- Edward Hopper, From Williamsburg Bridge

- Katsushika Hokusai, Under the Wave off Kanagawa

- Vincent van Gogh, Irises

- Claude Monet, Water Lilies

- Claude Monet, Bridge over a Pond of Water Lilies

- Albert Bierstadt, Merced River, Yosemite Valley

- Margareta Haverman, A Vase of Flowers

- Pierre-Auguste Cot, Springtime

- Winslow Homer, Northeaster

- Faith Ringgold, Freedom of Speech

- Paul Cézanne, The Gulf of Marseilles Seen from L'Estaque

- Edouard Vuillard, Garden at Vaucresson

- Romare Bearden, Tapestry "Recollection Pond"

- Camille Pissarro, The Boulevard Montmartre on a Winter Morning

- Henri Rousseau, The Repast of the Lion

- Edgar Degas, The Dance Class

- John Singer Sargent, Madame X (Madame Pierre Gautreau)

- Joseph Mallord William Turner, Venice, from the Porch of Madonna della Salute

Customize by size, choice of paper or canvas, and framing style.